Somewhere Nowhere Posted On 12th September 2019 To Magazine & Stories

In the midst of ever more sophisticated technology we live with the illusion of saving time by doing things with more speed, and increasingly relying on computers: programmes work out difficult problems, they plan for us, think for us. Files, servers and systems store information for us, including photographs - hundreds of millions of photographs.

A Slow Practice

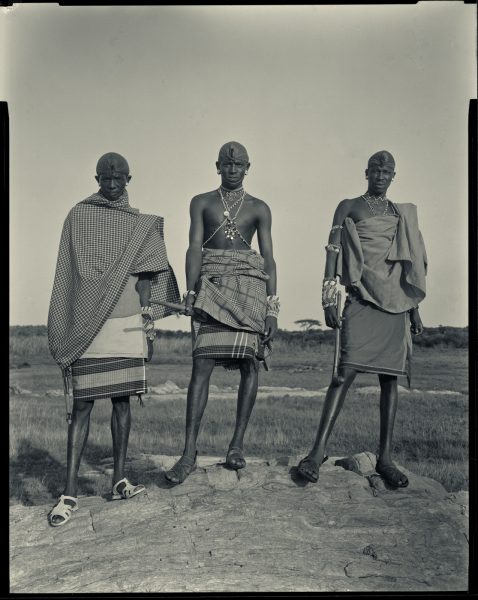

Samburu warriors, Kenya

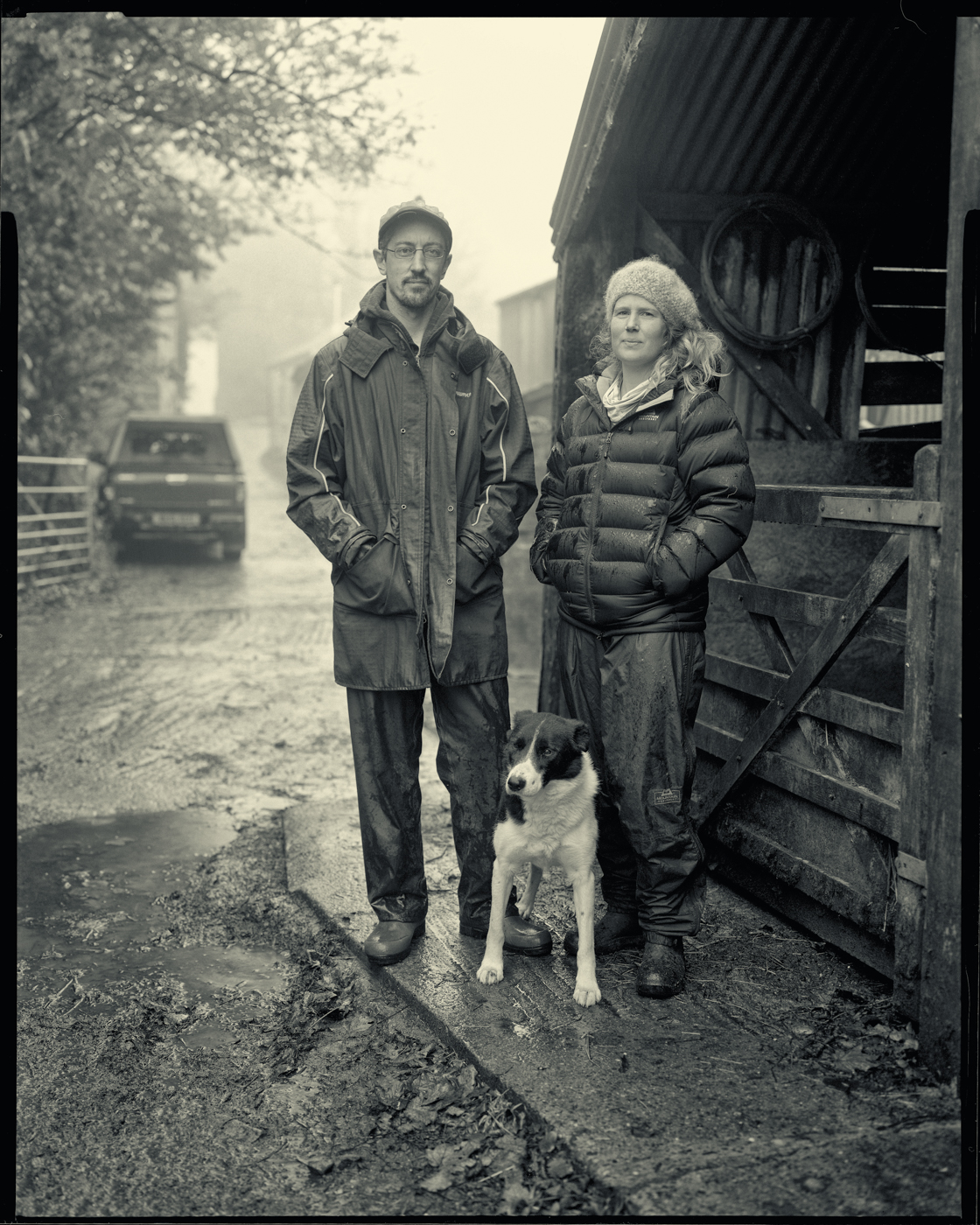

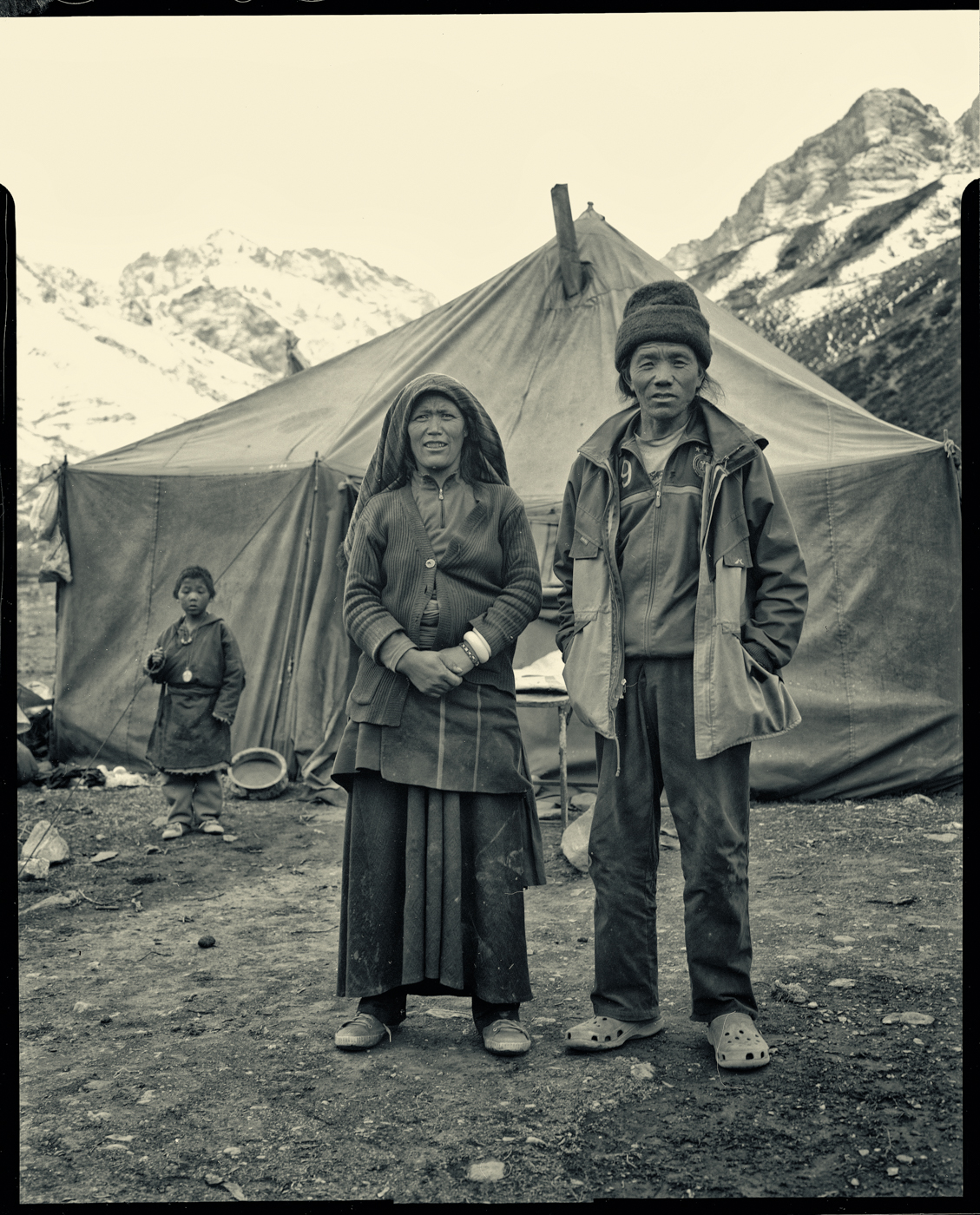

Rob Fraser is drawn to photograph people whose lives are shaped by traditional practices rooted in specific landscapes. Often their pace of life is slow, in cycle with the seasons, and Rob matches this with his own slow practice. Many of the people Rob chooses to photograph are on the edge of the physical and social landscape – on the ‘edgelands’ – and often on the fringes of other people's awareness. They hold a stillness and a sense of connection with traditions and crafts and, often, with ancestors whose lives have been similarly mapped out. The steadying constant is the land, their place in it, and the tasks they do because of where they are.

To capture all of this, Rob makes images with physical film – always ILFORD, invariably FP4+. The process, as well as the result, offer something more tangible and emotionally moving than a now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t digital image. And his traditional ‘large format’ film camera, whose functionality has barely changed since the early days of photography over a century ago, is necessarily slow. On average, it takes half a second to capture an image. That may seem fast but in photography terms it is sloth-like. The time taken to shoot a similar portrait using a digital camera might be around 1/125 of a second or, put another way, sixty times as fast. This is like extending a second so that it lasts a minute, or making a minute’s worth of attention last an hour.

Building Relationships

Making a photograph in this way can’t be done without striking up a relationship. Rob needs to spend time with the people he photographs (you can’t set up a large format camera, on its tripod, and stand there with a bright red cape over your head without first getting to know the people you’re going to shoot). The process of photography is also a process of kinship, talking, finding common ground. It may begin with a smile, or an introduction from a mutual friend. It may start with the sharing of a task. Always there is curiosity and an encounter of hearts and minds.

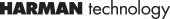

- Husband & Wife Porters, Pasang Doma Sherpa and Bim Tamang at Dingboche, Everest Region, Nepal

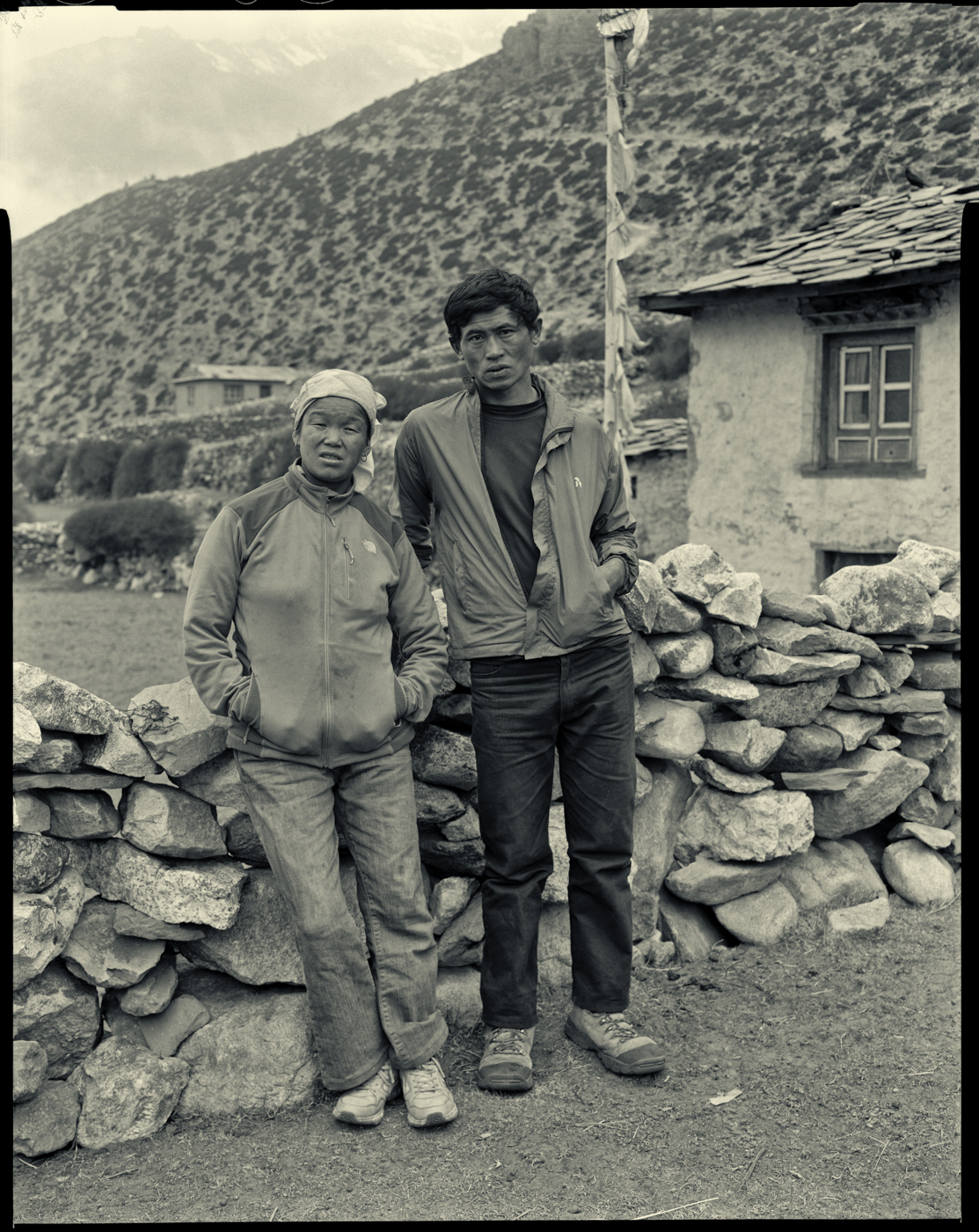

- Old Man – Hankar, Markha Valley, Northern India

Capturing Traditions

There is no long lens, no shooting from afar and a subject can’t be photographed unless they are ready, willing, and still. In large format photography something happens that extends beyond the act of photographing: there’s a resonance between photographer and subject and as the image is captured on a negative, a moment in time is stilled, marked out to last, and placed firmly in the memories of everyone who has been involved.

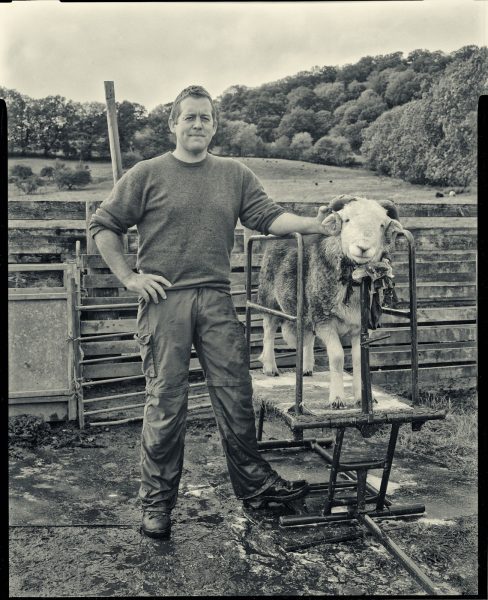

Hill Farmer James Rebanks Washing a Herdwick Tup in Preparation for the Autumn Sales

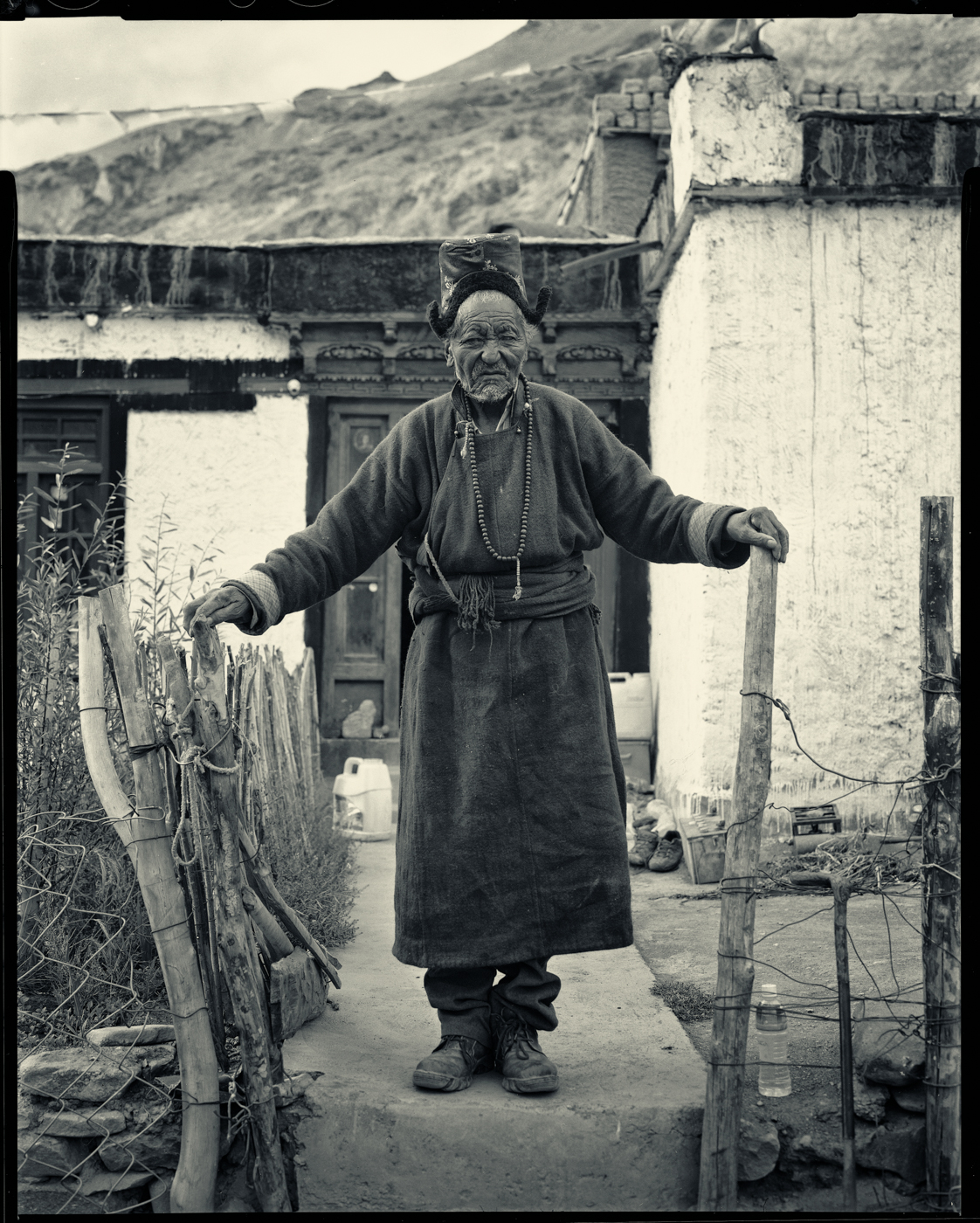

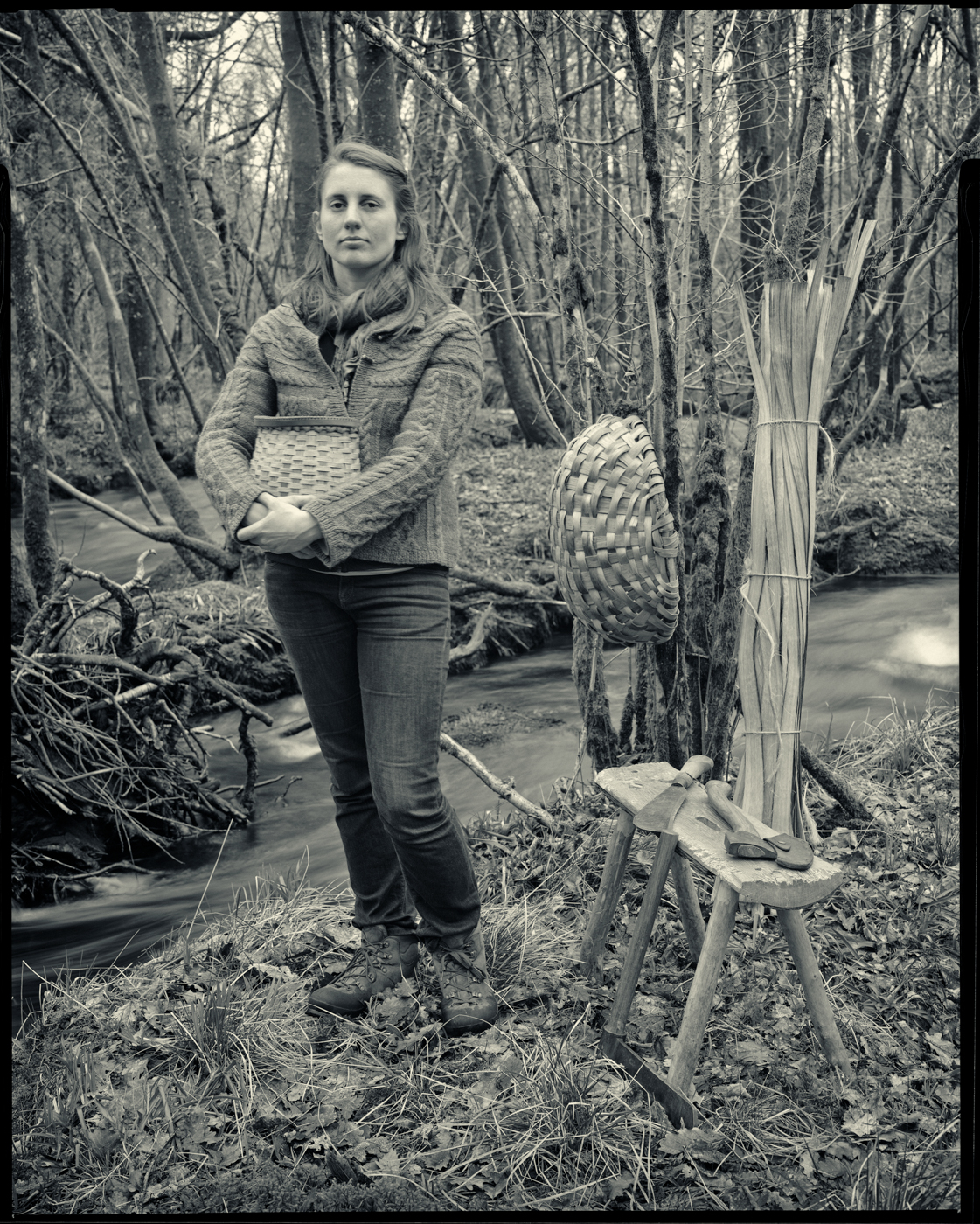

In the relationship that forms while an image is being made, stories are shared. The man whose dream it is to breed a 'perfect' Herdwick sheep, and whose best-selling book champions a tradition integrated with the land; the woman who leaves her five children for weeks on end while she works as a porter to give them the chance to choose a different path; the young woman who sits day after day in the woods with the trees that provide her with the material for her swills (traditional baskets made from strips of oak); the man who has lived in the mountains all of his life and slowly lost his sight; the teenager who has been working with horses in the Kazakh mountains since before he could walk.

- Horseman, Elyaman Jamalbai in Tien Shan Mountains, Kazakhstan

- Lorna Singleton, Oak Swill Basket Maker, Cumbria

Fixed in Place and Time

Editing in camera is key for Rob. The four edges of the negative frame the story and there is no post-production cropping. The final image may be printed life-size or bigger, so it’s possible to stand millimetres from the person who has been photographed and look straight into their eyes. There’s an invitation to pause, perhaps repeating the pause that existed when the photograph was taken, perhaps extending it. Another memory is created.

- Dartmoor Hill Farmers David Cole and Corrina Watson, Shot as Part of a Project Looking at Common Land Users

- Sonam LAmu & Galzin Tamang Have Lived in This Tent on the Edge of Shey, Dolpo – Western Nepal

For all of the slowing down of traditional photography, these images may be reproduced in digital format and will have their time on social networks. But their primary purpose is to exist as prints: light painted onto paper and fixed in place and time. Each photograph will exist in a limited number of prints to mark the value of the subjects - the people whose lives place them in the edgelands, sometimes through choice, often through birth. They keep their local connections strong and stand still in time. Meanwhile in the global community where lives are disconnected in time and space, voices and images are easily glossed over, forgotten in the blink of an eye.

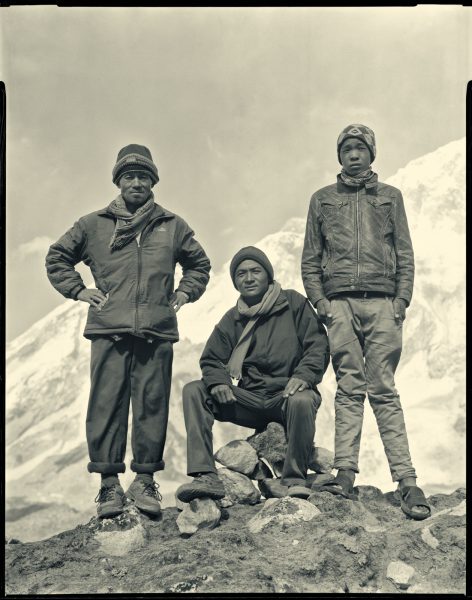

Three Porters, from left - Bim Badhur Tamang, Eka Badhu Rai, Kaji Sherpa at Gorak Shep - Everest

The Edgelands

The cultures thriving on the edgelands will change and adapt over time and some may pass. Capturing their lives and stories on film offers a tangible, emotional reminder of what is important now. Future generations may hold the prints in their hands even when the internet has failed.

Adapted from an article first published in Dark Mountain volume 8, Autumn 2015

About The Author

Rob Fraser

Rob Fraser has been making a living in one form or another from photography since 1981. Firstly, as a photo reporter for the Tenby Observer, then as a ground photographer for the RAF. He left the service in 1990 and turned freelance as a midlands-based location photographer.

Since moving to Cumbria and meeting his partner Harriet, a poet and a writer, his work has evolved to allow him to work on projects that tap into areas that he feels passionate about: the natural environment and how we as humans interact with place.

Rob and Harriet now collaborate creatively as somewhere-nowhere. Their work uses the power of curiosity and pause to engage with all the elements that give a sense of place, and let stories gradually reveal themselves. Sometimes these are stories of joy and celebration, sometimes they shed light on heritage. They may provoke further investigation or action, or touch on issues of struggle or loss in a local-global system where everything is connected, and balance can be elusive. Through photography and writing, with installations in rural spaces, they deliver creative projects that tap into and tell the stories of the natural environment and the people connected with it. They blend documentary with creativity and aim to inspire others to engage in debate and to go and find out more for themselves.

www.somewhere-nowhere.com

www.senseofhere.com

“I have always maintained that the best tool I carry around with me is not a camera (that comes a close second) – it is curiosity. I keep taking pictures because I am still curious. I keep pointing and I keep pressing the shutter. I am still loving the process of drawing with light. And I am still trying to show the wonder of the world as I see it.”

Rob Fraser