Light and Fathoms Posted On 24th December 2025 To Magazine & Stories

A black and white journey into the depths

When I leave home for a day of diving, I always feel a mix of excitement and detachment. A moment alone at dawn, when everyone is still asleep, becomes a kind of quiet ritual: methodically packing my gear, performing last checks, loading film and setting off towards a world apart.

My photography was born from a simple desire: to share those moments — their quiet magic, and the subtle mix of lightness and oppression that comes with the depths.

Swallowed by the beast (-48m) - Donator wreck, Port-Cros National Park. Nikonos RS with 13 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

I started diving as a teenager with my father in the South of France. These early mornings on the Mediterranean shaped everything that followed. From the start, I knew I didn’t want to make “fish close-ups.” No macro shots. No powerful strobes flattening the background into darkness. I wanted to photograph diving itself — the landscapes, the rarefying light, the divers who briefly inhabit them, — to capture our fleeting moments in a place where we don’t belong.

Big grouper bathing in the morning light, Port-Cros National Park. Nikonos V + 15 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400.

Why Film, Why Vintage

Years before I even thought about taking @ilm underwater, I bought a Rolleiflex out of curiosity, without realising I was acquiring what is still, in my eyes, the best camera ever built — both for its exceptional qualities and its limitations: one focal length, one film with fixed sensitivity, only twelve shots, and just two settings — aperture and speed. It taught me to become a better photographer

At that time, being of the digital era, I was using with a Nikon D800 in a housing, but the images didn’t re@lect what I was seeing or feeling during my dives. I kept looking for other solutions and eventually found one of the very rare Rolleimarin housings for Rollei@lex, my favourite cameras on land! It was my first experience with film underwater, and the resulting photographs remain amongst my most cherished.

But the Rolleimarin was still a land camera in a box — heavy, difficult to focus, and with a very narrow field of view. A 75 mm lens underwater is roughly equivalent to 90 mm which kept me quite limited to fish “portraits”.

“Le Sar”, emblem of the Mediterranean, probably puzzled by its own reflection on the flat dome port, Port-Cros National Park.

Rolleimarin - Rolleiflex 3.5F. Ilford Delta 400

My next step was naturally towards the Nikonos system. Born in the early 1960s, it remains the only truly dedicated underwater camera system. Its optics—water-contact wide angles like the 15 mm and the legendary 13 mm—were designed exclusively for underwater use. I particularily appreciate the Nikonos V understated presence: it fits in one hand and never hinders movement or compromise the safety of a dive. No distractions, no protruding arms to get tangled, nothing that prevents me from assisting a buddy, and no powerful lights blinding the sea life. Nothing in modern digital gear comes close, as I’m not ready to trade either the camera’s compactness or the almost organic grain I love for ultra-high ISO or the ability to shoot hundreds of frames in a single dive.

From left to right: Nikonos RS, Rolleimarin with Rolleiflex 3.5F, and Nikonos V with 15 mm.

Working with Light — or the Lack of it

As we immerse ourselves, light vanishes layer by layer, turning the sea into a monochrome world. The depths gradually block colours of the spectrum one by one — red, orange, yellow — until below twenty metres, nothing remains but shades of blue and grey. The grain, contrast, and tonality of black and white film express the atmosphere of my dives far better than any attempt to artificially recreate lost colours ever could.

I mostly shoot Delta 400, it covers nearly all my needs and responds quite well to underexposure and push processing. When I know the most interesting moments will happen deep — on a wreck, for example — I set the camera to underexpose by one stop (or two if needed) and push process at home. This flexibility makes the difference. On shallower rock dives, even if we start deep by dropping to forty metres, I know that most good frames will happen above twenty-five metres, where the light and sea life return, so I keep the best shots for the second half of the dive and stick to box speed.

“Hovering” pike on a dull November morning, Vodelée, Belgium. Nikonos RS with 13 mm lens, Ilford Delta 3200 (pulled 1 stop).

In Belgium, diving is different. Unless under exceptional conditions, quarries become pitch black from 10 meters deep, so I often use Ilford Delta 3200, pulled to 1600 ISO. The light is scarce, and the atmosphere is dense, sometimes almost claustrophobic. But the result can be striking: a diver emerging from the darkness, a fish caught in a beam of winter light.

A Hybrid Process

My workflow blends analog capture and digital finishing. After the dives, I develop the films at home, pushing or pulling depending on how the film was exposed. I love this part of the process. There’s a delicious frustration in not knowing what you’ve captured until you return and develop your film, sometimes weeks after the dive. It means each dive is lived twice: once underwater, and once in the darkroom.

Then I digitise the film using a Nikon D850 with 60mm Macro and an ES-2 reproduction setup. Once acquired in RAW, I make adjustments in Lightroom — just enough to clean up and bring out the tones.

The final image is high-resolution and ready to print or share. It’s still film — every bit of grain is there — but I can present it in a contemporary way. This hybrid approach allows me to enjoy the best of both worlds: the authenticity of film and the flexibility of digital.

The picturesque “Marcel” wreck under winter light, Hyères bay, France Nikonos V + 15 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

Living wrecks

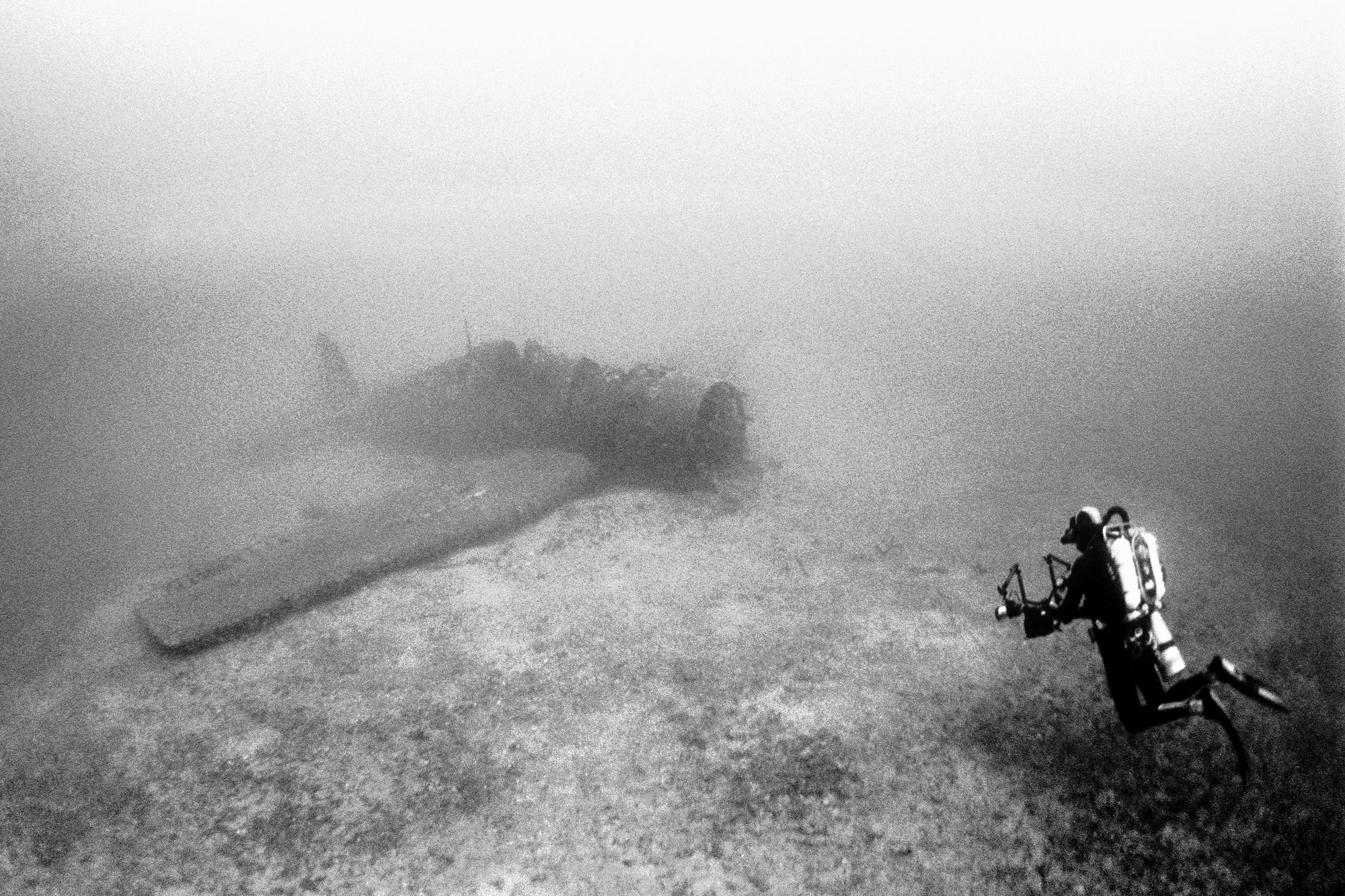

Of all the places I dive, wrecks are my favourite. They are not just physical structures; they are fragments of history and havens for marine life. Some have been on the seafloor for more than a century. They are silent witnesses to dramatic events: the Spahis, the Donator — ships lost in war or storm, now standing as oases in the desert of the seabed. Others, like the Hellcat, tell lighter stories: a French airforce pilot losing his propeller while playing “I dare you to fly lower than me” with his buddy, then ditching gracefully into the sea.

“Landing” on the Hellcat (-58m) - Pramousquier, France Nikonos RS - 13 mm. Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

Ship wrecks are both impressive and intimidating. They are places where the sea and human history meet. When I dive on a wreck, I always try to include a diver in the frame — to show scale, but also to anchor the image in the human experience.

Divers descending on the “Grec” (-44m), Port-Cros, France. Nikonos RS with 13 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

Unplanned Moments

Henri Cartier-Bresson once said that photography is the art of exclusion, and a perfect composition is rare. Underwater, this becomes very tangible.

I never dive with a plan or picture in mind, if the moment comes together, I take a picture. In full season there might be many divers and clubs on the same spot. The water alive with bubbles and passing fins. It is often hard to get a clear & clean shot. But that unpredictability is part of the story — and of the dive itself. I’m not staging scenes; I’m documenting what it feels like to be down there.

Every so often, I’m lucky enough to join quiet wreck dives with Frank, the owner of my club, who shares and understands my artistic approach. He knows these wrecks intimately — where to position, how to slip away from the beaten tracks. I can then fully concentrate on photography with minimal distractions: wait for the moment when the bubbles clear, when the wreck looms in stillness, when everything aligns in that window of time.

Frank inside the Donator wreck (-45m), Port-Cros, France. Nikonos V + 15 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

Different Waters, Different Cultures

Diving is not just about places. It’s about people.

In the South of France, where I learned to dive, many of the people I dive with are “old school.” They belong to a tradition not far removed from the pioneers of scuba diving. One characteristic is the use of spearfishing gear — two-piece “slim-fit” wetsuits that require soap to put on and long fins — a look inherited from earlier generations of divers that gives them a sleek shark-like silhouette underwater. To some modern divers it seems eccentric, and I often get questions about it from people around the world when I post images on social media. But visually, it has a real charm — a distinctive look that makes my photographs instantly recognisable.

Frank’s private tour of the Donator wreck (-47m) — Port-Cros, France. Nikonos V + 15 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

Belgium is another world entirely. It is a place where land and water blur into each other, where visibility is unpredictable and the light shifts from hour to hour. The gear is different — shaped by cold water, often 6 °C in winter. The divers are different too: here it’s more about the discipline itself than contemplation. The images are different as well. I like them equally, and the contrast between the two cultures feels almost alien — and creatively, very inspiring.

Gilles in side-mount (cave diving setup) chasing a sturgeon — Vodelée, Belgium. Nikonos RS + 13 mm lens, Ilford Delta 400 (pushed 1 stop).

Born of Water

It is a fortunate accident that my two passions ultimately aligned. Film photography, like diving, is born of water. Film emulsions are liquid at their core, and images emerge from the darkness of developer tanks — just as wrecks emerge from the shadows of the sea. Every photograph I make is shaped by water twice: once when it is captured, and again when it is revealed.

“Amour blanc” emerging from the fog - Rochefontaine, Belgium. Nikonos RS + 13 mm lens, Ilford Delta 3200 (pulled 1 stop).

All images ©Blaise Duchemin

About The Author

Blaise Duchemin

Blaise Duchemin is a film photographer and diver.

His work explores human presence in underwater landscapes, focusing on natural light and wide-angle compositions.

https://www.instagram.com/barnabeyphoto